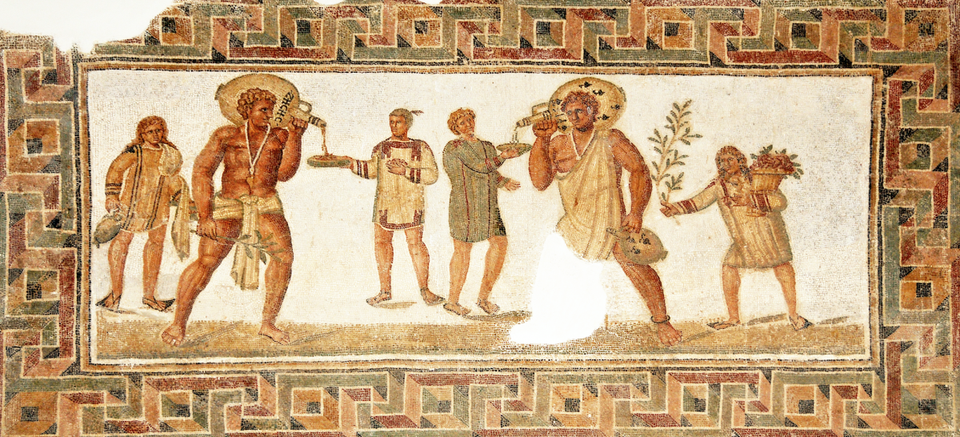

In ancient Rome, wine was far more than the drink of choice—it was a way of life, a civic virtue, and an economic powerhouse. Yet, in the 1980s, an American researcher threw a wrench into this well-aged narrative by suggesting that significant lead traces in the goblets used by Roman emperors could have been a factor in the empire’s decline and fall. This bombshell sparked a splash in the historical pond, opening up a debate that’s been raging ever since.

Wine in context

Before diving into these groundbreaking findings, let’s recall a famous line from the Roman historian Pliny the Elder on the subject: “Wine is the sunlight captured in water.” But if this sunlight was captured in lead containers, did the sun leave a toxic aftertaste in every glass? He may not have enjoyed as much insight into this than modern science, but he certainly had a point there. The problem, however, was than drinking wine was a bit of a requirement for Rome’s high class. “Water drinkers” were viewed with the utmost suspicion. The poet Horace famously said that no good poet ever drank water!

It was a little harsher than that. There was a widespread belief at the time that wine revealed true intentions. Showing that you could get hammered was often a question of honour, as it was believed that wine revealed your true intentions.

To be fair, those were probably pretty good for their times. The Romans, like the Egyptians before them, had their own grand crus, such as the prestigious Falernian wine.

Lead in Pottery: A Hint of Death in Daily Life

Now lets talk about lead, pipes and poisonning.

Over 5,000 years ago, the area around Rome was already familiar with lead. This versatile material played a crucial role in ancient infrastructure and daily life, giving the Latin word plumbum, which evolved into the term “plumbing”. Indeed, the Romans were well-versed in the use of lead. It was not only a protective layer for aqueducts but also a frequent component of high-quality vases and containers.

Lead was believed to possess medical properties, or at least beneficial effects on the body: it was added to cosmetics, and medicines, and even used as a food preservative. Roman pottery, with its shining lead-based glaze, was a common sight across the empire. From amphoras to drinking cups, lead was often the secret ingredient. Modern analyses have shown that acidic wine could slowly dissolve the lead, blending it into the drink of the gods.

An Empire Steeped in Lead!

The Romans were literally making lead juice. With their vast quantities of grapes, Roman citizens crafted a sweet syrup by heating wine in lead-made pots! Lead ions would seep into the juice, combining with acetate from the grapes. The resulting syrup was exceedingly sweet and used in wines as well as a variety of foods.

Out of 450 recipes in a cookbook from that era (the cookbook of Apicius), 100 mentioned the use of these syrups. Romans were also fond of their wine, with aristocrats consuming between 1 and 5 liters each day. Researchers who have recreated some of these syrups found lead concentrations about 60 times higher than what the EPA allows in public drinking water. (Small caveat to this, Romans and Greeks usually diluted their wine into 2 to 3 parts of water, so no, your average Roman intellectual didn’t go around slurring all day long)

Did Lead-Laced Wine Cause the Fall of the Roman Empire?

We have had evidence of the harmful health effects of lead exposure since 1943. But the notion of a direct link between this exposure and a civilizational cataclysm was proposed by geochemist Jerome Nriagu in a controversial 1983 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. He argued that lead poisoning played a significant role in the downfall of Rome.

Nriagu, using available data on wine consumption and the lead content in cups used by the Roman elite, extrapolated the empire-wide exposure averages to arrive at a rather alarming conclusion. His estimates suggested that the average Roman was exposed to a dangerously high amount of lead. He concluded that chronic lead ingestion caused widespread health problems among the Roman aristocracy, including gout, mental decline, and infertility, contributing to the decline of Roman society.

His thesis was quickly (and angrily) criticized by leading Roman history scholars, primarily for misinterpreting classical sources. Nriagu relied on secondary sources to support his arguments, notably citing the Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus through a 19th-century gastronomic work, interpreting writings literally to claim that saturnine gout, a manifestation of lead poisoning, was prevalent among the Roman aristocracy.

Criticism intensified with other experts, like Waldron, pointing out Nriagu’s oversimplification in attributing Rome’s complex decline to a single cause. Nriagu defended his approach against critics, but his methods raised valid questions about the reliability of his sources and interpretations. For instance, his use of a translation of Musonius Rufus to assert the ubiquity of gout among Roman elites, without considering more authoritative translations, shows some negligence in critically examining his materials.

Smoke and Mirrors? Not So Fast!

Although the biochemist’s findings were sharply dismissed, a consensus exists about the dangers of lead. Several subsequent studies have highlighted the omnipresent danger of lead among Romans without identifying it as an empire-scale threat. However, compelling evidence does suggest that lead posed a real danger to public health in everyday life.

Consider the example of sapa, a grape juice concentrate used as a sweetener, often prepared in lead vessels. Given the Romans’ sweet tooth and the scarcity and expense of honey and sugar cane, using a type of lead as a sweetener was common, potentially leading to significant lead exposure among the Roman population.

On the other hand, research on the effects of lead on the health of Roman children revealed a negative correlation between death age and lead concentrations in dental enamel, suggesting that lead poisoning contributed to high infant mortality and morbidity in the Roman world.

Overall, evidence suggests that lead contamination was relatively limited compared to today’s averages. Studies on the lead content in Roman-era skeletons show that it peaked at only 41-47% of the levels found in modern Europeans, suggesting that chronic lead poisoning did not significantly contribute to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The Fall of the Empire: A Mix of Factors

Certainly, pinning the fall of the Roman Empire solely on lead poisoning oversimplifies the issue. As historian Edward Gibbon pointed out, Rome’s collapse was a “gradual and complex process.” Lead might have been just one of many drops in the already overflowing barrel of social, economic, and political issues.

Let’s also remember that the Roman Empire faced a series of crises leading to its final dissolution: the succession crises of the third century, the migratory pressures from well-armed nomadic groups, the disappearance of public funds due to corruption, the personalization of Roman power, and the internal wars of the 4th and 5th centuries, among others.

In conclusion, whether lead contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire remains an open debate. However, one thing is certain: Roman pottery, as gleaming as it may be, may hide a darker story than we’ve imagined. So, the next time you’re sipping on a glass of wine, you might want to ask yourself: “Do I really want a bit of lead in my wine?” The choice is yours, hopefully as wise as the Romans’.

Cheers, and don’t forget to raise your glass to history, even if it’s sometimes a bit heavy with lead!

Relevant Sources on the Fall of Rome

- S. C. Bradford, Drinking and Sobriety in Ancient Rome (2008).

- J. S. Werner, The Romans and Their World: A Short Introduction (2010).

- J. K. Evans, Have a Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks (1999).

- M. Beard, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (2015).

- D. S. Potter, A Companion to the Roman Empire (2006).

- M. Grant, The History of Rome (1978).

- P. Garnsey, Food and Society in Classical Antiquity (1999).

- R. Laurence, Roman Pompeii: Space and Society (1994).

- E. Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776).

- H. Flower, Roman Republics (2010).

- F. Retief, L. Cilliers, Lead poisoning in ancient Rome, (2010).

- Joanna Moore, K. Filipek, V. Kalenderian, Death metal: Evidence for the impact of lead poisoning on childhood health within the Roman Empire, (2021).

- Som Sharma, Charu Sharma, Lead Poisoning – The Roman Scenario and Today’s World, (2016).

Pierre-Olivier Bussières est l’auteur du podcast Le Temps d’une Bière, producteur de Hoppy History et rédacteur en chef du média Le Temps d’une Bière. Il détient un diplôme d’études supérieures en sciences politiques de l’Université Carleton.

Leave a Reply