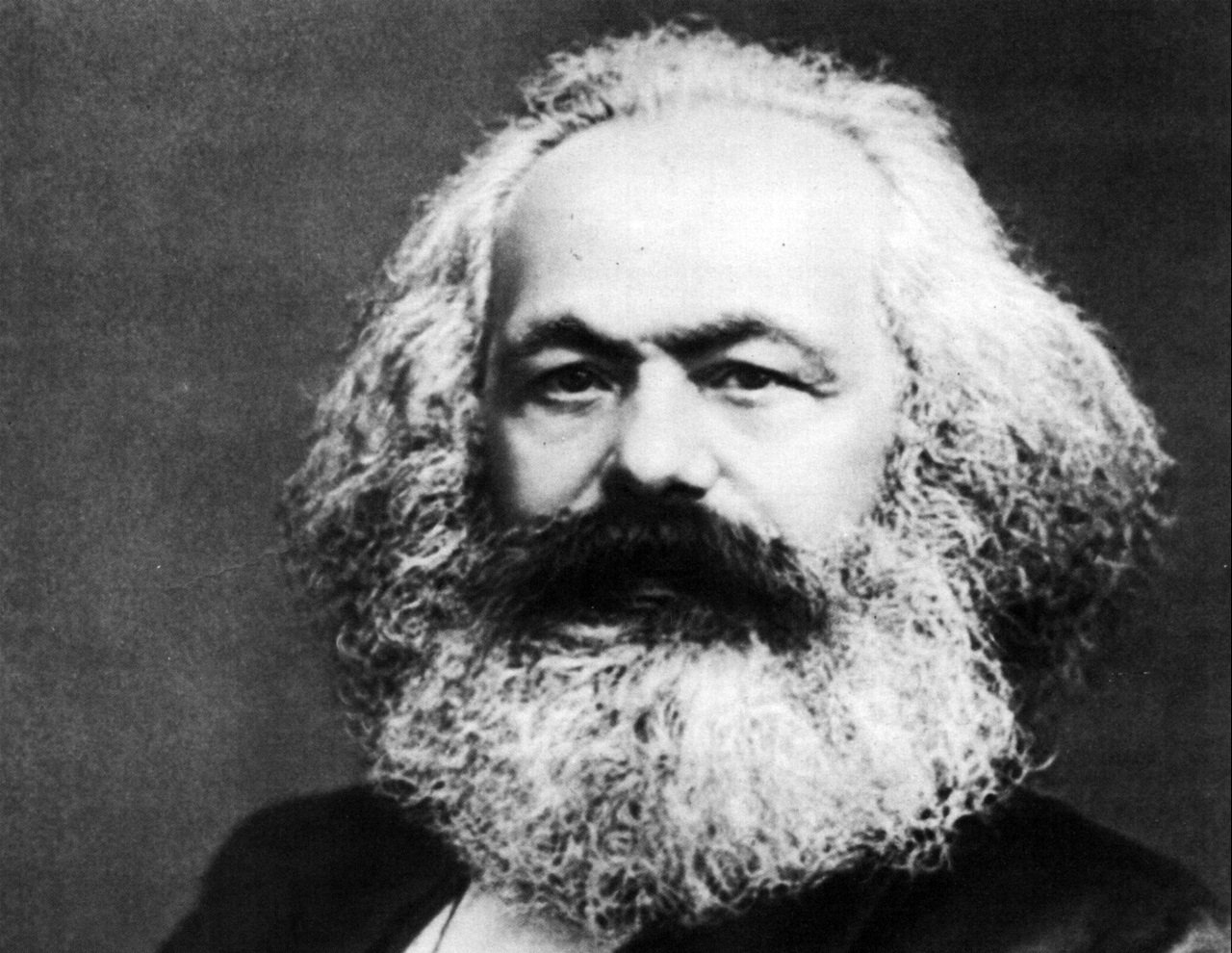

Karl Marx: philosopher, revolutionary, and champion imbiber! Our bearded radical cultivated not only class consciousness but also a remarkable tolerance for alcohol, likely honed during his wild university days in Bonn. By 1849, Marx’s liver was staging its own internal revolution against his decadent bourgeois habits.

When not penning manifestos, Marx could be found holding court in Europe’s smoky taverns and cafés—the original social networks for 19th-century intellectuals with a flair for the dramatic. His other constant companion? A never-ending parade of cheap cigars that would make even the most dedicated tobacco lobbyist wince.

In perhaps the darkest irony of dialectical materialism, Marx’s writings occasionally waxed poetic about poison as an exit strategy—a grim philosophy that would later find tragic disciples in two of his daughters. Seems the family approach to problem-solving took rather literal forms of « radical » solutions!

A heavy drinking student

Marx acquired a reputation as a turbulent drinker at a young age in Bonn and later in Berlin, where he pursued his university studies at the age of 17. Some biographers theorize that he even became the president of a drinking society, but this is not entirely accurate, considering that most student societies inherently engaged in drinking.

However, we know that it was precisely due to his bar-hopping escapades that Marx’s father, Heinrich, compelled his son to leave the city of Bonn. A Prussian intelligence agent described the young Marx as follows: « He leads the life of a true Bohemian intellectual (…) Washing, grooming, and changing his clothes are things he rarely does, and he enjoys getting drunk. »

When Heinrich sent him to Berlin, Karl Marx continued to demand substantial sums from his parents to maintain his expensive lifestyle. Most of that money ended up paying for hearty meals and drinking nights. Despite his father’s warnings, Marx persisted in frequenting biergartens and taverns. Political speeches and drinks frequently escalated into brawls, with Marx often at the forefront, indeed often the instigator of the conflicts.

In a famous drinking episode, Marx found himself naked in the Spree River, rescued from drowning by more sober fellow students. During a heavily intoxicated evening in London, Marx got into a brawl with his former friend Edgar Bauer after boldly declaring that everything done in Germany was superior.

His English socialist friends did not appreciate this, leading to a general altercation. On another occasion, in a cheerful mood, Marx rode a donkey down the main street of a small village, smashing lights with a friend before making a quick escape to evade the police.

What did Karl Marx drink?

Marx was initially a wine enthusiast. The Marx family owned a large vineyard on the slopes of the Moselle. These vineyards provided young Marx with his first lessons on the excesses of capitalism. The customs union with Prussia had just been imposed, with devastating effects on local winegrowers like his father. Marx remained a staunch critic of the family vineyards for the rest of his life.

Indeed, the introduction of cheaper Bavarian wines to the local market ruined local producers. By denouncing this invasion of southern wine, Marx first made a name of himself by producing furious pamphlets about the demise of his region’s merchants. Many were very happy to read, and support articles, denouncing Prussia’s commercial imperialism.

Marx had a particular fondness for Bordeaux wines, as did his wife Jenny. In fact, his friend Engels sometimes sent them by mail. These little gifts were funded by the textile factory that Engels disliked but which covered Marx’s and his family’s expenses. Engels himself had a preference for Margaux.

Beer also ranked high on the list; it was affordable and served as a liquid meal. Marx, who spent half of his life as a refugee, first in Paris and then in London, struggled to earn a living. Beer, more calorific than today, served as a cheap, makeshift meal. It was common in certain industries and liberal professions to drink « on the job. »

Paris: Cabarets, Cafés and Communism

In 1844, the icon of the workers’ revolution was in Paris at the age of 25. He was young, curious, inquisitive, fervent, but also impatient, anxious, lost, and in exile. He had left the German Rhineland to escape censorship. After breaking the ice in German breweries, Marx discovered Parisian cafes and cabarets. It was in this surreal, electrifying atmosphere that his political thought took shape.

Ironically, people didn’t frequent the « Café » for coffee at that time. The hot beverage was ridiculously expensive and still tasted somewhat like burnt coal. There was nothing of the modern barista. The coffee was crushed rather than ground and calcined rather than roasted. As coffee didn’t please everyone, many other liquid delights were offered. Cafés served beer, wine, grog, orange juice, lemonade, and absinthe, which was then a novelty.

It’s unclear if Marx indulged in the green fairy, but the coffee was undoubtedly a morning ritual. Since Marx often stayed up late writing, it’s a safe bet that he consumed considerable amounts. Paul Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law, and a committed socialist wrote that Marx invariably took it black and early in the morning.

During ten days of rare inebriation there, Marx formed an alliance with his future companion: Friedrich Engels. Two extremely important things emerged from that week and a half for Marx’s legend: the Paris Manuscripts, outlining the foundations of his economic and political thought, and Engels’ unwavering support. If Marx had the means of sedition, it was Engels who provided the means of publication.

It is impossible to accurately describe what the City of Light meant for an intellectual of that time. Paris was the cultural capital of Europe, the scholarly beacon of literature, and the political lung of the continent. Being in Paris meant reigning over history. Paris was the Mecca for socialists, anarchists, and liberal reformists. Its streets teemed with secret societies devoted to overturning the Order, the « system. » In Paris, Marx found a face for his enemy and a formula for his cause.

In Paris, Marx also found himself surrounded by a legion of Germans who had also left their homeland. They constituted the largest foreign minority in Paris. Many were political refugees, others economic refugees. The increasing industrialization of the Rhineland, as in Paris, created misery for artisans. People organized as best they could to grab remaining jobs. At the same time, they planned the new republic, exalted the values of liberalism, and described the excesses of the current regime.

Marx threw himself heart and soul into everything France wrote and thought. He read like a demon, spent entire nights transcribing texts, paced back and forth reciting crucial quotes, rewrote the same sentence forty-eight times to sharpen its precision, defaced volumes by groping in the dark, and piled up mountains of matches to revive a forgotten cigar.

His curiosity was frenetic, inexorable, and formidable. As soon as he began a chapter, he had to find three new books and comment on them all. His publishers would reproach him his entire life for never finishing anything on time and for scattering himself on insoluble questions. He was scattered across a thousand projects that never came to fruition.

Ten Well-Soaked Days with Engels

This is where Friedrich Engels comes into the picture. The man who would later become his closest friend arrives in Paris after a stay in Manchester, where his family owned a prosperous textile factory. Engels was the quintessential bourgeois of his time: pampered, overeducated, and a bon vivant. But he was also burdened by the guilt of his class. He was methodical, precise, and calculated – the opposite of Marx, who was disjointed, candid, and satirical.

Since the two men had read each other and mutually approved through correspondence, their meeting was inevitable. In this early autumn of 1844 in Paris, over many pints, a philosophical love affair blossoms. Marx and Engels spent ten days together in Paris, thoroughly soaking themselves in beer. Tristram Hunt, who has written a new biography of Engels, described their encounter as « ten days steeped in beer. »

The cafes of Paris were a unique breed among the various drinking establishments where revolutionary ideas ferment. Unlike cabarets, they were not the exclusive domain of the elite. Like taverns, there was a café for every class, and a class for every café. Many went there to brew ideas, mischief, and conspiracies.

Karl Marx: Advocate for the People’s Beer

One thing is certain: Marx was a staunch political ally for beer. In 1855, he wrote in support of a popular demonstration against the Beer Bill, an English law that closed all public entertainment venues on Sundays, except between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. Here’s what he had to say:

This bill was quietly introduced at the end of a sparsely attended session, after pietists secured the support of London’s major pub owners by assuring them that the licensing system would continue, meaning that big capital would retain its monopoly.

Marx also added theory to practice. In Volume 1 of Capital, Chapter 24, the little father of communism notes the capitalists’ tendency to lower workers’ wages. He cited, among others, an 18th-century author unfairly criticizing the lower classes for indulging in the bottle:

« But if our poor » (a technical term for workers) « wish to live luxuriously… then labor must, of course, be dear… When we consider the luxuries that the manufacturing working population consumes, such as brandy, gin, tea, sugar, foreign fruits, strong beer, printed calicoes, snuff, tobacco, etc. »

Despite the legend, Marx’ political activity often clashed with other socialist projects. Even as he wrote the Communist Manifesto, deep divides existed between different socialist groups vying for the forefront of the workers’ cause. Beyond the alcohol of those days, the revolutionary passion was perhaps the most potent intoxicant of the times.

Sources

- “Karl Marx.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Karl-Marx.

- “Work Is the Curse of the Drinking Classes” Lapham’s Quarterly

- “Karl Marx’s views on wine” This day in wine History

- “A Prole’s Guide to Drinking” Troy Patterson, Slate

- “Karl Marx : A nineteeth century life” Jonathan Sperber

- « Karl Marx: A Life » Francis Wheen

- « Karl Marx: A Biography » David McLellan

- « Marx: A Very Short Introduction » Peter Singer

- « Karl Marx: His Life and Environment » Isaiah Berlin

Pierre-Olivier Bussières is the Editor-in-Chief of Hoppy History and Uber Optimized. He is the Sales and Marketing Director at Uberflix Studio. He also writes about travel, geopolitics, and alcohol markets, and has published articles in The Diplomat, Reflets, The Main, Go Nomad, Global Risk Insights, and Diplomatie.

Laisser un commentaire